Before Two Wars: Munich, Creating and Collecting

In part two of this series, Abigail Leali traces how politics, architecture, and collecting shaped Munich’s artistic identity through institutions and history, not just individual creators

Abigail Leali / MutualArt

Jul 25, 2025

When the average person on the street thinks of art history, their mind usually turns to artists. Michelangelo, da Vinci, Monet, Picasso – individual men (and, to the extent social convention has allowed, women). To their innate sparks of talent, we have attributed the sacred progress of culture’s divine flame from generation to generation. If the goal is simply to appreciate the work, that idea will probably serve just fine.

But if the goal is really to understand art – its material, its themes, its evolution, its purpose – the endeavor quickly becomes far messier. The myth of the individual genius may seem to disappear in a fog of dubious financial ties, political machinations, and mixed motives. After all, the truly “starving artist” would quickly die. If we want to understand how Munich came to be the cultural icon we know today, we need to look beyond talented individuals and explore the countless historical influences that allowed its unique artistic identity to take root.

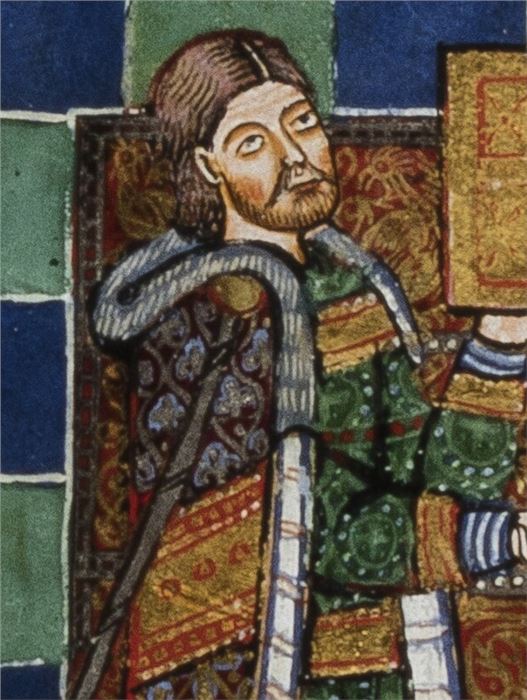

Though archaeologists have found evidence of Munich’s location being occupied since the Bronze Age, the city as we know it had quite a definite beginning. In 1157, according to surviving documents, Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony and Bavaria, granted the nearby Benedictine monastery permission to start a market and erect a new bridge over the Isar River. After some political maneuvering, the town would be founded (to the best of our knowledge) on June 14, 1158. From there, it took fewer than twenty years for the strategically placed market to burgeon into a fortified city, and when Emperor Frederick Barbarossa had him vengefully deposed in 1180, Bavaria entered what would become the 700-year dynasty of the Wittelsbach family.

det. Gospel of Henry the Lion, 12th c.

As the giants rained thunder upon each other overhead, the little city of Munich endured centuries of expansion and collapse, including not only wars and political intrigue but also multiple major fires that ravaged the city’s early architecture and a devastating outbreak of the Black Death in 1349. It wasn’t until the 1400s – following a period of sustained support from Duke Louis IV, a citizen of Munich who was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 1328 – that the city finally gained enough strength and stability to begin establishing itself as a cultural and artistic center.

None of these key figures in Munich’s history were artists (though some, like Henry the Lion, were patrons of the arts). But as much as we may like to envision the future glory of Munich as a triumph of what is most ideal and beautiful in the human spirit, the reality is that it all could just as easily not have happened. The twists of fortune that allowed Munich to form also tilled its soil, preparing it for the artistic explosion that was about to begin.

.jpg)

Alter Peter, 2014 (photo by Richard Huber, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Gothic and early Renaissance periods in Munich saw the birth of some of the first cultural icons we can still find in the city today. Most prominent among them are Old St. Peter’s Church near Marienplatz and Frauenkirche.

.jpg) Frauenkirche, view from Alter Peter, 2006 (photo by Diliff, CC BY 2.5)

Frauenkirche, view from Alter Peter, 2006 (photo by Diliff, CC BY 2.5)

Current archaeological evidence suggests that a church has existed on the spot of St. Peter’s since well before the city’s founding, but the church as we see it today was dedicated in 1368 after its predecessor was destroyed in a fire. To this Bavarian Romanesque base, later architects would add a Renaissance steeple – and even later, a variety of Baroque elements.

Frauenkirche, on the other hand, was built in only a couple of decades. Architect Jörg von Halsbach began the project in 1468, and Pope Sixtus IV granted an indulgence for its completion when money ran out in 1479. The church was dedicated in 1494, though due to additional financial constraints, the two iconic domes (potentially inspired by Byzantine architecture) would not be added until 1525.

It is difficult to imagine what Munich would look like without these churches, which would form an integral part of the backdrop for all of the city’s subsequent cultural movements. Even artists and thinkers antithetical to the churches’ Catholic roots would try to claim their evident significance. In 1919, the Bavarian Socialist Republic, a brief and ultimately failed leftist movement, would deem it a temple to their revolution.

%2c%202007%20(photo%20by%20gerhard%20blank%2c%20cc%20by-sa%203.0).jpg) Aerial view of old town (Munich), 2007 (photo by Gerhard Blank, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Aerial view of old town (Munich), 2007 (photo by Gerhard Blank, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In these two structures, Romanesque and Gothic, we see the beginnings of Munich’s unique creative genius – that which, more than any individual artist, would contribute to its thriving culture of beauty. The city may not have originated architectural movements, but it was beginning to curate them, bringing them together to develop one dramatic cityscape, an homage to the best of the European artistic tradition.

And, while architects were taking influence from abroad to craft their structures, the ruling Wittelsbach family was not sitting idle. Alongside their official political duties, they were also beginning to collect an increasingly elaborate “cabinet of curiosities,” which was housed in the famous Munich Residenz. In 1571, Wilhelm Egkl and Jacobo Strada completed the Hall of Antiquities (Antiquarium) to display Duke Albrecht V’s growing collection of pieces from Greece, Rome, Egypt, and beyond – it was the largest Renaissance hall ever built north of the Alps. Albrecht V, along with his father before him, commissioned artwork, amassed jewelry and coins, and worked on the ducal library. While still far from public view, their efforts formed the basis of the Wittelsbach collections.

.jpg) Residenzstraße, Westfassade der Residenz, 2012 (photo by AHert, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Residenzstraße, Westfassade der Residenz, 2012 (photo by AHert, CC BY-SA 3.0)

From the period of Munich’s founding to the early days of the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s, there were not many individual artists who stepped above the fray to achieve lasting acclaim. (A notable exception would be Jan Polack, a presumably Polish-born artist whose surviving Gothic masterpieces still hang in Munich today.) And yet, all we have covered here has set the stage for Munich to become a thriving cultural sphere. Though it lagged behind the Mediterranean in adopting Renaissance principles, it established a pattern: one of taking what is best from an artistic tradition and integrating it into its own collection. Old St. Peter’s and Frauenkirche were soon to be joined by – and ornamented with – some of the richest examples of the Baroque Counter-Reformation. The Wittelsbach collections in the Munich Residenz were to keep growing, forming the financial basis for centuries of artistic flourishing that have culminated today in many of Munich’s most famous museums, including the Alte Pinakothek.

Jan Polack, Weihenstephaner Altar, Der hl. Benedikt als Vater des abendländischen Mönchtums Rückseite, Kreuzannagelung Christi, 1483-89 (photo by Alte Pinakothek, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Munich is one city among untold thousands throughout history, and its evolution from Benedictine monastery into sprawling architectural achievement may seem to have been as much an accident of history as a triumph by any man or group of men. But, as I was researching this article, I was also struck by the number of names we do know, from political figures and patrons to artists and architects. Munich, like all cities, has been built up by the daily lives and choices of everyone who lives there, a collective endeavor that has a life outside the purview of any one person. At the same time, it would be wrong to ignore the outsized importance of those few key figures, whose talent, authority, or simply money gave them the opportunity to influence their culture more than others of their generation.

Certainly, few if any of the men we’ve discussed today could claim to be saints or even to act outside of their own self-interest. “To whom much is given, much is required” – if we are (rightfully) quick to censure those in power when they abuse it, we must also be ready to admit when they use it well. No one exists in a vacuum, but some names echo far beyond it.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page