Turning Infrastructure into Art: Rackstraw Downes and Valeri Larko

Urban decay and industrial remnants become poetic subjects, urging viewers to look more deeply

Kristen Osborne-Bartucca / MutualArt

Aug 08, 2025

In 1967, artist Robert Smithson took a bus ride through Passaic, New Jersey. In the essay that resulted, A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey, Smithson wrote of the ruins of late capitalism that dotted the landscape – defunct machinery that looked like “prehistoric creatures trapped in the mud,” bland used car lots, concrete abutments, a pumping derrick. His subtitle for the essay wondered, “Has Passaic replaced Rome as the eternal city?” which, while tongue-in-cheek, suggested that Smithson was looking at the city from a much different perspective than most artists. The sites he identified and photographed in the essay were far from aesthetically pleasing, and in fact were ones that most people would probably purposefully ignore. For him, a city’s modern “monuments” weren’t skyscrapers or statues but rather the structures that exemplified capitalism in its amorality and appetite.

Smithson was one of several artists in the mid-late 20th century who were interested in abandoned, derelict urban spaces and the banal infrastructure that undergirded the city. For a time, these artists all tended to be photographers, utilizing the medium’s documentary function to explore and critique their environs.

But in the last decades of the 20th century, a handful of painters, particularly in New York, also began turning their attention to ruins and remnants, infrastructural systems and sites both operating and defunct. Their works did not include people, but the traces of people are pervasive.

This article will consider the work of two of these painters, Rackstraw Downes and Valeri Larko, and how and why their works illuminate sides of the city that most people would consider inconsequential or unsightly.

Rackstraw Downes (b. 1939)

Rackstraw Downes, born and trained as an artist in England and naturalized as a U.S. citizen, is known for his panoramic, en plein air paintings of urban environs. He spends months at a time on site, drawing and painting with nary a camera in sight. Eschewing the term “realist,” he nonetheless tackles subjects that seem relentlessly, oppressively real – underpasses and offramps, buildings under construction, sewage plants, pedestrian bridges, and the like. Critic Donald Kuspit writes in Artforum that Downes is a “theatrical genius” because he “quite subtly crafts a sweeping stage upon which nature may make a last-ditch appearance before it is crushed under the weight of the urban environment – a landscape of anonymous and intimidating buildings holding life and death in their balance.”

But critic John Yau views Downes as someone who looks ethically and empirically, who avoids the binary of the picturesque, sentimental urban ruin and the emphatically offensive one. Echoing Smithson, Downes wrote in 1992 that when he first saw the industrial landscape of Jersey, he “looked, and did not think of things as good or bad, but as present. Garbage and sewage and industrial effluent are characteristic of the landscape we all helped to make. Structures rusting in the New Jersey Meadowlands are to U.S. industrial might as the tombs and aqueducts of the Campagna are to the Roman empire.”

Rackstraw Downes, A Fence at the Periphery of a Jersey City Scrap Metal Yard, 1993. Oil on canvas.

Rackstraw Downes, A Fence at the Periphery of a Jersey City Scrap Metal Yard, 1993. Oil on canvas.

Fence, 1993, is an excellent example of Downes’ style and preferred subject matter. It is resolutely horizontal, with an imperfect perspective that nonetheless mimics the way the world curves around our vision. The two World Trade towers are visible far in the background, inconsequential and incidental. Instead, the eye is drawn to the long, arcing fence at the center of the canvas which is framed by slender telephone poles and wires above and golden yellow, overgrown weeds below.

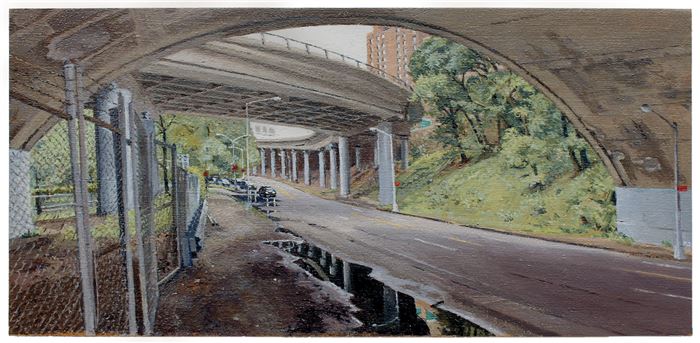

Rackstraw Downes, Under the J Line at Alabama Avenue, 2007. Oil on canvas.

Rackstraw Downes, Under the J Line at Alabama Avenue, 2007. Oil on canvas.

Chain-link fences, fetid puddles of roadside water, and aging concrete overpasses populate this work featuring Brooklyn elevated train and highway infrastructure. Though the title tells us where this was painted, it really could be any urban road. The cars about to zoom by, their headlights gleaming on the wet asphalt, will probably not think twice about what they see, but Downes and the viewers of this painting undertake “looking” in a much different way.

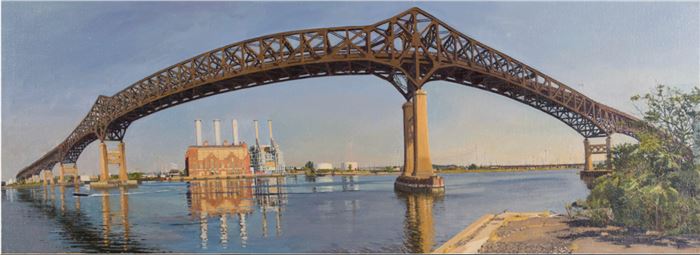

Rackstraw Downes, The Pulaski Skyway Crossing the Hackensack River, 2007. Oil on canvas.

Rackstraw Downes, The Pulaski Skyway Crossing the Hackensack River, 2007. Oil on canvas.

In this work Downes simultaneously makes the viewer appreciate the marvels of modern engineering and also concede that much of the time those marvels are visually unappealing. The skyway is heavy, rusted, and severe. In the background is the Kearny Power Plant, another structure embodying the modern city. The skyway’s dominance of the sky and the plant’s reflection in the water call back to Kuspit’s claim that nature struggles to assert itself in the face of modern industry.

Valeri Larko (b. 1960)

Larko was raised and trained as an artist in New Jersey, painting industrial parks and salvage yards throughout the state for many years. She then moved to New Rochelle in the Bronx and continued to paint cityscapes, all done en plein air and with emphatic verisimilitude, that captured the borough’s built environment and how it was always threatening to teeter into obsolescence. Larko explains that she has “always been interested in how the most ordinary things, things we overlook,” and “regarding the abandoned sites, I’m interested in places that are about to disappear, the stories these places can tell about our recent past and where we are headed.” Her scenes of the Bronx include businesses that have closed, their boarded-up fronts splashed with graffiti; billboards with often ludicrous slogans amid moldering environs; brutalist underpasses and train trestles; the Gowanus Canal; an abandoned golf center; and many more scenes of urban decay. Like Downes, Larko does not romanticize these scenes, but neither does she intend us to find them repulsive. Rather, we are cognizant of the hopes and dreams embodied and lost in the now vacant buildings.

Valeri Larko, Rusting Gantries, 2008. Oil on linen.

Valeri Larko, Rusting Gantries, 2008. Oil on linen.

Two rusting gantries loom above the viewer, their original purpose stilled and their surroundings now totally grown over with weeds. In Monuments, Smithson wrote of “a Utopia minus a bottom, a place where the machines are idle, and the sun has turned to glass” – a perfect way to describe Larko’s scene. What once no doubt seemed grand and useful is now moribund, a literal monument to late capitalism’s relentless technological advancement, to its creation of what Smithson calls “ruins in reverse” in which “the buildings don’t fall into ruin after they are built but rather rise into ruin before they are built.”

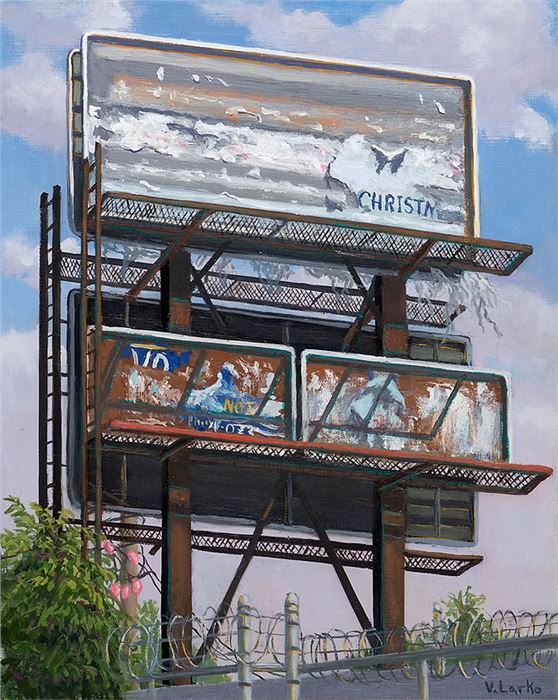

Valeri Larko, Signs of the times XXXI (Rusted Billboards), 2023. Oil on panel.

In many of the billboards from Larko’s Signs of the Times series, the advertisement is still there, shouting out questions or advice (“Shackled by lust? Jesus sets free” “Violence is NOT a solution” “Injured? 1-800-HURT-511” “In the beginning God created.”), but in others such as XXI (Rusted Billboards), there is no text anymore, only a palimpsest of former slogans and suggestions. Like her abandoned buildings and infrastructure, these empty billboards attest to the ephemerality of human endeavors.

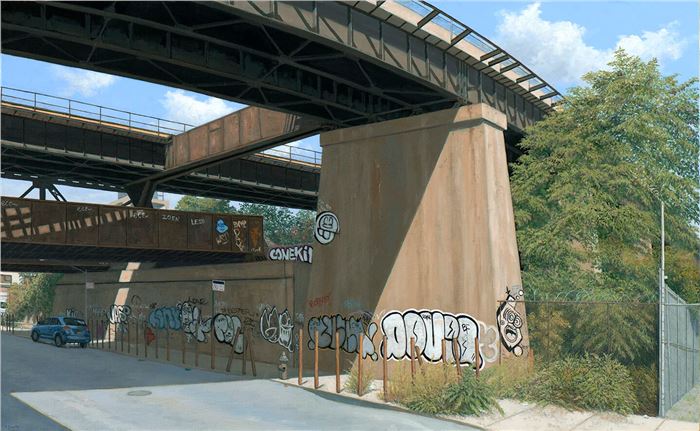

Valeri Larko, Train Trestle, East 133rd Street, Bronx, 2016, oil on linen.

Valeri Larko, Train Trestle, East 133rd Street, Bronx, 2016, oil on linen.

Similar to Downes’ scenes of the nondescript city streets underneath bridges and highways, here Larko shows us something quotidian that nonetheless rewards us for sustained looking. We see what she saw: interplays of sun and shadow, tenacious plants that refuse to be contained by fences or sidewalks, inscrutable graffiti, traces of people going from here to there.

Downes and Larko choose subjects that show the struggle between nature and industry; that testify to the ease with which human endeavors fail; to bleak and uninspiring urban environments that many of us navigate daily. But as the examples of their work reveal, they are not pessimistic or savagely critical; rather, they ask their viewers to be patient, open-minded, and contemplative. This sort of looking is perhaps not easy, but they seem to suggest, it is both meditative and restorative.

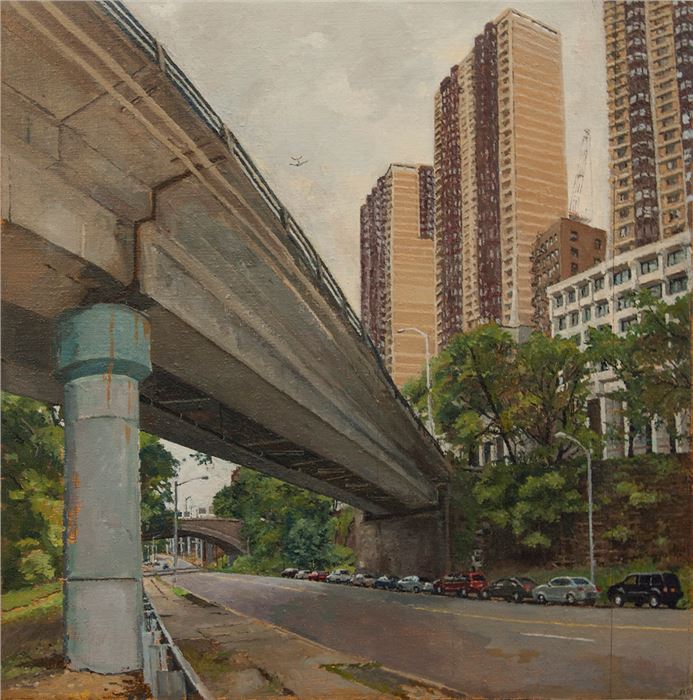

Rackstraw Downes, George Washington Bridge Exit Ramp Over Riverside Drive, NYC, 2015, oil on linen.

Rackstraw Downes, George Washington Bridge Exit Ramp Over Riverside Drive, NYC, 2015, oil on linen.

Similar to J Line, 2007, this work shows a nondescript street underneath a highway, this time the exit ramp from a bridge into upper Manhattan.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page